#14: The camera leaves out the bigger picture

Plus five things I've loved this past week (many thought-provoking links!) and a book giveaway for subscribers

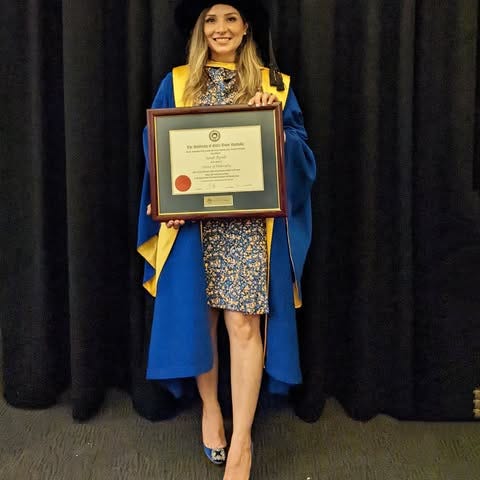

In the weeks following my PhD graduation, I felt really bummed out. I had built the day up in my head in the lead-up to it: in the moments when writing my thesis felt really difficult and I visualised its completion (especially during the pandemic, when I had two kids at home and was pregnant with my third); when I found the perfect dress to wear a year before I submitted my thesis; the day I picked up my doctoral regalia and gushed about the Tudor bonnet in whats app messages to my sisters; and in the time spent thinking about the party I’d planned to host after the ceremony was over.

It wasn’t until I really sat with my feelings that I realised that I was not quite disappointed with how the day itself went but with the lack of evidence that it had even occurred. I had imagined a highlight reel of the day: a video of myself getting ready in the morning, a big, look-at-me-I-did-it smile as I put on my hat; pictures with my kids before I dashed off to the event; selfies with my fellow graduands as we waited for the ceremony to commence. None of those moments eventuated: the day was so busy on account of an early start and torrential rain; I left my phone with my mother during the ceremony; I didn’t want to cancel my afternoon uni classes so I left fast to take them before I went to the after-party and didn’t take a posed portrait with the hired photography team. Apart from the official photograph taken as my degree was conferred on me with my supervisor by my side, and a haphazard photo my mum took of me afterwards in one of the crowded rooms of Sydney Town Hall, the graduation day did not earn the kind of coverage on my social media, or even in my phone’s photo album, that could warrant it a special enough event.

I had been looking forward to that day for so so long, and yet I had more photos in my phone of me holding a cookie and a Frank Green cup while in mary-jane flats than I did of myself on the day I became a Doctor (of Philosophy). It was almost like it didn’t happen.

Last week, the New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission approved the installation of a gate in front of the Manhattan brownstone at 66 Perry St, a location made famous because it was the pretend exterior of Carrie Bradshaw’s Sex and the City apartment (the character’s official address is 245 E 73rd Street, but Perry St had a better facade). The owner of the brownstone was fed up with the hordes of tourists, sometimes in the bus loads, queuing up at all hours of the day for a photo on that now infamous stoop. Some, she revealed, went all the way up to the doors and windows of the place, making the building’s residents and neighbours increasingly uncomfortable.

Of course, this is not an issue that is exclusive to Carrie’s stoop, but to tourist destinations more broadly: last year, the city of Fujikawaguchiko in Japan announced the installation of a mesh net measuring 2.5 metres high and 20 metres in length (the length of a cricket pitch, if you need to visualise it) in front of Mt Fuji. In pursuit of the perfect shot — one that was ubiquitous on social media — tourists were “littering”, “ignoring traffic regulations” and “overcrowding a stretch of pavement” in a way that locals deemed disrespectful. The barrier, officials said, was regrettable but necessary, a reflection of “badly behaved” tourists, all in pursuit of a photo, as opposed to an experience. (They could see Mt Fuji from so many other angles; this particular one, in front of a Lawson Convenience Store, was definitely about earning a sort of social media tick of approval.)

The comment section of the Times article was kind of wild, with people venting about those who take up space for the sake of a good photo. I wondered if I found it wild because I was an elder millennial who had spent years uploading so much of her life online, and kind of understood the reasoning behind the right shot, even if I never managed to capture it myself (*cries looking at photos of me at age 22 with the Leaning Tower of Pisa, taken in the wrong light*). I’d caught the tailend of MySpace and once thought it normal to upload hundreds of photos of a night out to Facebook; I’d built the beginnings of my career thanks to a now-defunct blog where I chronicled things I did and bought; I shared opinions I probably wouldn’t back today on a Twitter account I no longer use. I’ve now spent so much of my time on Instagram that going to the app feels increasingly habitual and unconscious as opposed to intentional and considered.

And yet, despite having lived what I would call a big life, I didn’t have much to show for it on my Instagram page, which mainly included photos of the books I was reading and sometimes the outfits I was wearing. I had taken numerous overseas trips, to photo-worthy destinations like Rome, Paris, Florence, Venice, London, Berlin, Dubrovnik, Budapest, Santorini, Kyoto, Hong Kong, Beirut (and many more), but I lacked the evidence of this. None of my photos were nice, properly proportioned, appropriately edited. That was if they even existed (I’ve lost too many photos because I’ve not backed up). Did my trips still count?

If someone were browsing my socials, then probably not. In moments of insecurity brought on by these very apps, I wondered if people knew the truth: that I have indeed lived a big life, but that I didn’t have the skill to capture the perfect photo, or the patience to wait around for a crowd to disperse at the expense of actually seeing the place I was there to see.

So much has been written about what we post on social media, and I am not going to repeat it here. I am writing about this because it’s another example of how pervasive the need to document everything is, often at the risk of actually living in the moment, and how even the most rational and contemplative among us can fall into the trap of needing external validation when we ourselves know we’d been there, seen that. I could sit down with someone and tell them the best place to get a schnitzel in Vienna, what the baths in Budapest are really like, and where to get a really excellent gelato in Rome. But these things lack currency when they’re not followed up with the visuals: me in the perfect outfit, holding said gelato. I seemed to be sandwiched between Gen Z who documented everything digitally (and looked good doing it) and Gen X who printed out all manner of photos without considering where the right spot was; devices and backing up be damned.

I’m thinking about all this right now because I have once again had a twinge of regret over my graduation day, and all the photos I could have taken while in my Tudor bonnet. If I had though, I wouldn’t have had the conversation with the student next to me, who I’d never seen on campus before but who turned out to be from a Lebanese village so close to mine. I would not have had the time to take in all the intricate details of the historical building we were in, or reflect on how lucky I was to have the supervisor I did, and did she get new glasses?

But I am also thinking about it because I have (at this point temporarily) deleted the Instagram app from my phone, and there are so many temptations to upload photos of my days, even if they’re of no relevance to anyone, simply because I got the perfect shot of my breakfast with my current read or my kids running amok in the local park, hashtag Sydney summer. What strikes me most is the fleeting thought that these moments hold little weight if they’re not shared, as if putting them out there validates them in here (*points to heart*) when in reality, I have to build myself up so much more inwardly if I am ever going to be OK with how I am out there.

Of course, there are so many cases for putting the phone down and enjoying the moment, or not feeling the need to share it with the world. But as a creative, the biggest reason is what those pictures do to our memories and our creative muscles. There’s a reason our attention spans are shorter: we just can’t process the way that we used to, and processing is essential for creating. Sans picture, I have space to dream, to embellish, to make more out of my lived experience. Without the concrete details of a photo, I can add a little depth and colour to the memory, forcing myself to recollect what existed outside the frame. Pictures are definite, they leave no room for imagination, they relieve our brains of work that is actually good for them. Manually recollecting forces us to switch on, to make more of the moment, and the nostalgia of memory actually aids creative writing.

Pictures are great until you realise they get in the way of noticing, and noticing is what makes us better writers. Sticking my face behind a camera, or jostling with a crowd with my phone in my hand, is only going to get in the way of the sensorial detail I should be paying attention to: it risks my missing the way a Chinese tourist holds her parents or stops me wondering about the meanings behind the carvings in the stone. Ironically, the camera leaves out the bigger picture we might otherwise take in: a picture might tell a thousand words, but daring to go without one paves the way for an actual story.

Five things I have loved this past week:

My friend Karima’s perfect manoushie dough. I ate zaatar breakfast pizza everyday for four days afterwards. Making it with her while our kids played in her backyard gave me serious Lebanese village vibes, and it was amazing.

Sitting in my armchair reading cookbooks while drinking mocktails at night; sitting in my armchair reading novels while having tea and scones by day.

Borrowing! I picked up Zoe Foster Blake’s new book and Nina Kenwood’s The Wedding Forecast from the local library; joined Kanopy to watch My Salinger Year, and downloaded Love Stories on My Borrow Box.

Great online reads. Like the big, 8000-word Vanity Fair feature on Meghan and Harry, this piece by Anna Wharton and this essay for After Babel, where ‘gen Z writer’ Freya India discusses her generation’s anemoia, or “nostalgia for a time or a place” they have never known. This nostalgia, she says, manifests in their fascination with polaroids, vintage cameras, VHS tapes and 90s high school graduation videos, and is born out of a grief for emotions and experiences her generation will never understand, like the excitement and anticipation for a new episode of a favourite TV show, or being able to sit in the sadness of a tragic news story, without them being “drenched in endless opinions online”. She writes: “New technologies cheapen and undermine every basic human value. Friendship, family, love, self-worth—all have been recast and commodified by the new digital world: by constant connectivity, by apps and algorithms, by increasingly solitary platforms and video games. I watch these ‘90s videos, and I have the overwhelming sense that something has been lost. Something communal, something joyous, something simple.” Also highly recommended: this essay by Hayley Nahman which really, really resonated, and this case for being bored.

This first episode of Kristin Davis’ new podcast Are you a Charlotte?, which is perfect for fans of the original Sex and the City for all its behind the scenes.

A new book, my latest articles and a subscriber giveaway

I’m in The Guardian this week with two articles: one looking at the role that music plays in helping children adjust to ‘big school’ and the other with some titbits from parents on surviving the school holidays (which if you’re in NSW, seem exceptionally long this year).

I have also just announced the release of my new (very commercial) children’s picture book, All The Ways Mum Will Be There For You, out in March with HarperCollins. If you have little ones in your life, consider pre-ordering or requesting your local library buys a copy.

Finally, I’m giving one subscriber the chance to win a stack of four fabulous 2024 reads by culturally-diverse women. They encompass literary fiction, auto-fiction, non-fiction and middle-grade fantasy, and are guaranteed to be great reads. They are Translations by Jumaana Abdu; Dirt Poor Islanders by Winnie Dunn; Cactus Pear For My Beloved by Samah Sabawi and How To Free A Jinn by Raidah Shah Idil. This giveaway is open to Australian subscribers only (sorry!) and all you have to do is leave a comment on this post and I will put you into the draw. Competition closes Thursday 30th January at 6pm AEDT. Good luck, and as always, thanks for reading!

I feel so much of this, too. I got off Instagram in November last year, and only go back on here and there to see what writing updates there are, but that's it. And it's been freeing and anxiety inducing all at the same time. Like, what if I miss something?! Or, sadly, I know I won't have the same connections with this person if I am off socials. But, you know, a healthier mind takes priority and, like you said, I finally get to notice the little things and really be in the moment. Thanks for writing this, Sarah! Your newsletters are always so, so relatable.

I relate to so much of this. I went to London and Paris last year, but intentionally kept it off social media, because I didn't want people to know I was there and wonder why I hadn't reached out. And I remember writing back in 2012, shortly before joining Instagram, that one reason I was skeptical of the platform is that I didn't want my life to feel like a constant performance for the camera. I've also temporarily deleted it from my phone in protest of its founder's kowtowing to the new US president, and have found myself noting how many times a day I go to reach to check it.